Abstract

The aim of this study is to investigate the correlation between soft drusen and the likelihood of mortality from all causes and specific ailments within a representative United States population. This cohort study encompassed 4497 individuals from the 2005 to 2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) cycles, and followed for survival to December 31, 2019. Data on soft drusen were obtained from fundus images. Survey-weighted Cox regression models were utilized to evaluate the hazard of soft drusen incidence and mortality. After a median follow-up of 12.33 (11.33, 12.58) years, 1014 (22.5%) patients died from all causes. Overall, individuals with soft drusen exhibited an increased risk for all-cause mortality (HR 1.41; 95% CI 1.22 to 1.64), cardiovascular disease (CVD)-related death (HR 1.53; 95% CI 1.15 to 2.04), and mortality from other causes (HR 1.48; 95% CI 1.20 to 1.83). Further stratified analysis revealed that the mortality rates were heightened in participants who had distinct soft drusen or both types of soft drusen, as well as those with soft drusen measuring 500 μm or more in diameter. The investigation revealed that soft drusen was linked to all-cause mortality, CVD mortality, and mortality resulting from non-cardiovascular and non-cancerous conditions, indicating that soft drusen may symbolize frailty and aging processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drusen are extracellular debris deposits that accumulate beneath the retinal pigment epithelium with age1. These deposits serve as diagnostic indicators for various diseases, including age-related macular degeneration (AMD)2, cardiovascular disorders (CVD)3, Alzheimer’s disease (AD)4, and dense deposit disease5. While drusen may be associated with these and other diseases, the mechanisms underlying drusen development remain poorly understood.

Studies have shown that individuals with moderate to large drusen have an estimated 18% probability of progressing to late-stage AMD within five years6. Previous research has extensively explored the relationship between AMD and survival outcomes, but the results have been inconsistent7,8,9,10. Most studies have focused on the correlation between AMD and mortality specifically related to cardiovascular disease. Soft drusen, an early indicator of high risk for AMD, has been associated with various systemic health conditions; however, its implications for overall mortality are not well understood. A comprehensive understanding of the link between soft drusen and specific causes of death could provide insights into the pathophysiology of AMD.

Therefore, we aimed to investigate the association between soft drusen and mortality using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Methods

Design and participants

The NHANES is a comprehensive initiative designed to evaluate the health and dietary conditions of individuals in the United States. It operates through a biennial survey that employs a nationally representative sample design to gather pertinent data11. The NHANES adheres to the ethical guidelines of the National Center for Health Statistics research ethics review board, aligning with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration, and secured written consent from all participants12.

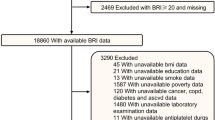

For our analysis, we utilized data from 2005 to 2008 NHANES cycles, focusing on individuals aged 40 years and older, totaling 7081 persons. We excluded 2584 individuals due to ungraded retinal images, missing drusen data, missing covariate data, or missing death data, resulting in a final sample of 4497 persons (Fig. 1).

Retinal photography and soft drusen grading

During the 2005–2008 period of NHANES, retinal photographs were collected from individuals aged 40 and above. When retinal images were available for both eyes, the data from the worse eye were used. Soft drusen are classified into three categories based on their characteristics: soft distinct drusen, soft indistinct drusen, and the presence of both types of soft drusen. The diameter of soft drusen also plays a role in their classification. Soft drusen are categorized into three types based on their diameter: <125 μm, 125–500 μm, and ≥ 500 μm.

Mortality data

The mortality data was extracted from the 2019 Public Access Link Mortality dataset which linked with the National Death Index by a specific ID. During the study period, all participants were followed until December 31, 201913. Any participant not matched to a death record was considered alive for the entire follow-up period. Causes of death encompassed any fatalities arising from any source. Utilizing the Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases-10 codes, cardiovascular deaths were identified within the categories I00-I09, I11, I13, I20-I51, and I60-I69. Cancer deaths were classified under C00-C97, and all remaining cases were attributed to other causes of mortality. The survival of the participants was computed by measuring the interval from the time of the interview to either the occurrence of death or the endpoint of December 31, 2019.

Covariates data

Factors such as age, gender, race, educational level, marital status, family income, body mass index (BMI), alcohol consumption, and smoking habit were collected through household interviews14,15. Age groups were set as 40 to 60 years and above 60 years. Ethnicity was classified into non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, other Hispanic, or other races encompassing Multiracial. Educational level was bifurcated into less than a high school diploma and a high school diploma or higher qualification. Marital status was either married or cohabiting with a partner, or unmarried or in any other relationship status. The poverty income ratio (PIR) was assessed as below the poverty line (PIR < 1) or at or above it (PIR ≥ 1). Alcohol consumption was classified into non-drinkers, those who consume 1–5 drinks monthly, 5–10 drinks monthly, and over 10 drinks monthly. Smoking patterns were classified as non-smokers, former smokers, or current smokers.

BMI was divided into underweight (less than 18.5), normal to overweight (18.5–30.0), and obese (equal to or exceeding 30.0). Diabetes was confirmed through a glycosylated hemoglobin level, a fasting plasma glucose level, a self-reported doctor’s diagnosis, or insulin usage. Hypertension was identified if an individual had a past history of hypertension reported, or a systolic blood pressure reading of 130 mmHg or more and/or a diastolic blood pressure of 80 mmHg or higher, based on the average of four measurements. CVD encompassed congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease, angina, myocardial infarction, and stroke. Walking impairment was self-reported as difficulty in walking or dependence on special aids for assistance. Health status was classified into two groups: poor to fair and good to excellent. Ocular coexisting conditions were defined as the presence of cataracts, glaucoma, or retinopathy.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluations were conducted considering the intricate and stratified structure of NHANES, adhering to the NHANES guidelines for analysis and reporting. Descriptive statistics are depicted as mean ± standard deviation for continuous data and as counts and proportions for categorical data. To contrast the baseline attributes between individuals with and without soft drusen, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and a chi-square test, corrected by Rao & Scott’s second-order method, were employed. Only statistically significant covariates were incorporated into the multiple Cox regression model for adjustment purposes.

The analysis of differences in mortality age between the group with soft drusen and the one without involved employing the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, along with assessing the time elapsed to death from the initial examination. The comparison of mortality rates between these two groups was carried out using Fisher’s exact test.

Survival probabilities and their corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) were assessed using standardized survey-weighted Cox proportional hazards models adjusting for age, gender, racial background, family income, educational attainment, hypertension, cardiovascular conditions, walking difficulties, self-reported health status, history of cancer, and ocular co-morbidities, which calculated hazard ratio (HR)14. Separate models, also survey-weighted and were employed to evaluate the impact of various soft drusen conditions and diameters on survival.

Data analysis was conducted using R software, specifically version 4.3.1, released on June 16, 2023, with the ucrt package. A two-tailed P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

Results

In the 2005–2008 NHANES, there were 7081 participants aged 40 years or older. This study excluded 2584 NHANES participants with ungraded retinal images, missing drusen data, missing covariate data, and missing death data, resulting in a final sample of 4497 participants for analysis.

Of the enrolled population, 767 (17.1%) had soft drusen at the baseline examination, whereas 3730 (82.9%) did not have soft drusen. Table 1 presents the demographic attributes, health-related behaviors, and prevalent health comorbidities of the total participant cohort, as well as those with and without soft drusen. Participants with soft drusen were older than those without soft drusen (62.7 ± 0.5 vs. 54.5 ± 0.2 years), and a higher proportion were male (52.0% vs. 47.0%). More participants with soft drusen had hypertension (72.0% vs. 60.0%), CVD (18.0% vs. 9.3%), and walking disorders (9.6% vs. 6.5%). They were also more likely to report poor to fair health status (20.0% vs. 16.0%), more likely to have cancer (15.0% vs. 11.0%), and more likely to have eye complications (31.0% vs. 18.0%) (Table 1).

Mortality characteristics

After a median follow-up of 12.33 (11.33, 12.58) years, 1014 (22.5%) participants died from all causes. The all-cause mortality rate in the soft drusen group was 38.0%, significantly higher than the 19.0% in the non-soft drusen group (P < 0.05). Analysis focusing on specific causes revealed a higher mortality risk in individuals with soft drusen compared to those without, irrespective of whether the cause was cardiovascular disease (CVD) or any other non-CVD or non-cancer cause (Table 2).

Stratified analyses were performed according to soft drusen status. Of the 1,014 participants who died, 723 (71.3%) had no soft drusen, 170 (16.8%) had soft distinct drusen, 25 (2.5%) had soft indistinct drusen, and 96 (9.5%) had both types of soft drusen. The all-cause mortality rates were 33.0%, 34.0%, and 53.0%, respectively, all higher than the 19.0% in the non-soft drusen group (P < 0.05). The age at death in the soft distinct drusen and both soft drusen groups was higher than in the non-soft drusen group (P < 0.05). No substantial variation was observed in the time from baseline assessment to mortality among the three categories of soft drusen groups and the group without soft drusen (P > 0.05) (Table S1).

Participants were also classified according to soft drusen diameter. Of the 1,014 people who died from all causes, 723 (71.3%) had no soft drusen, 97 (9.6%) had < 125 μm soft drusen, 95 (9.4%) had 125 to 500 μm soft drusen, and 97 (9.6%) had ≥ 500 μm soft drusen. The all-cause mortality rates were 29.0%, 36.0%, 60.0%, respectively, all higher than the 19.0% in the non-soft drusen group (P < 0.05). The average age of death from all causes was 79.0 ± 1.1, 80.0 ± 0.9, and 83.0 ± 0.9 years, respectively, showing a gradual upward trend. Each soft drusen group was older at the time of death than the non-soft drusen group (76.0 ± 0.4 years) (P < 0.05). There was no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) in the duration from initial assessment to all-cause mortality between groups with varying degrees of soft drusen and those without soft drusen (Table S2).

Table S3 presents the correlation analysis between baseline variables and survival outcomes. Males exhibited an increased likelihood of all-cause mortality (HR 1.42; 95% CI 1.25 to 1.62; P < 0.05). After adjusting for age and sex in Cox proportional hazards regression models, several factors were significantly associated with heightened all-cause mortality risks, including race, PIR, educational level, BMI, marital status, alcohol consumption, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, CVD, walking disability, self-rated health, cancer, and the presence of comorbid ocular diseases (all P values < 0.05).

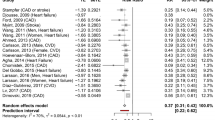

Cause-specific mortality

Among the 1014 deaths, 235 (23.2%) were due to CVD, 250 (24.7%) to cancer, and 529 (52.2%) to causes other than CVD or cancer. Several adjusted survey-weighted Cox proportional hazards models revealed an increased mortality risk among individuals with soft drusen compared to those without (HR 1.41; 95% CI 1.22 to 1.64; P < 0.05). When examining cause-specific deaths, the presence of soft drusen was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of death from cardiovascular disease (HR 1.53; 95% CI 1.15 to 2.04; P < 0.05) and non-cardiovascular or non-cancer-related causes (HR 1.48; 95% CI 1.20 to 1.83; P < 0.05). However, no significant association was observed with cancer-related mortality (HR 1.19; 95% CI 0.77 to 1.83; P > 0.05).

Stratified analysis by the presence of soft drusen status revealed a heightened mortality risk among individuals with soft distinct drusen (HR 1.26; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.49; P < 0.05) and those with both soft drusen (HR 1.81; 95% CI 1.44 to 2.27; P < 0.05). Both soft distinct drusen and the presence of both types of soft drusen were linked to increased risks of death due to cardiovascular disease (HR for soft distinct drusen: 1.48; 95% CI 1.08 to 2.02; HR for both types of soft drusen: 1.76; 95% CI 1.05 to 2.95) as well as other causes (HR for soft distinct drusen: 1.26; 95% CI 1.04 to 1.53; HR for both types of soft drusen: 2.13; 95% CI 1.55 to 2.94).

Analysis stratified by the size of soft drusen revealed that participants with a soft drusen diameter of 500 μm or more exhibited an elevated mortality risk of all cause (HR 1.90; 95% CI 1.44 to 2.50; P < 0.05), CVD cause (HR 1.82; 95% CI 1.03 to 3.24), and other causes (HR 2.34; 95% CI 1.55 to 3.53) (Table 3)

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis revealed that all subgroup HR estimates exceeded 1, aligning with the primary findings of this investigation. Despite the HR for individuals with a BMI under 18.5 (HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.09 to 1.99, P > 0.05) and those below the poverty line (HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.62, P > 0.05) being less than unity, the non-significant P-values indicate the robustness of our model (Fig. S1).

Discussion

In a comprehensive national study involving 4497 American adults aged 40 and above, we revealed significant findings regarding mortality risk linked to soft drusen. Individuals presenting with soft drusen exhibited higher all-cause mortality, CVD mortality, and non-CVD or cancer-related mortality. Further analysis segmented by soft drusen status disclosed an augmented risk of all-cause mortality among participants with distinct soft drusen as well as those exhibiting both types of soft drusen. Notably, distinct soft drusen and both types of soft drusen were found to be connected with CVD mortality and non-CVD or cancer-related mortality. Additionally, our investigation stratified by the diameter of soft drusen indicated that subjects with soft drusen measuring 500 μm or more had a heightened risk of all-cause mortality compared to those without such drusen. Importantly, a soft drusen diameter of 500 μm or larger was also linked to fatalities due to CVD and non-CVD or cancer-related causes.

With the progression of age, soft drusen form as accumulations of extracellular material underneath the retinal pigment epithelium16. Subjects with moderate and large drusen have an estimated probability of 18% progression to late AMD over five years6. Numerous investigations consistently reveal a higher likelihood of all-cause mortality in individuals with late AMD, echoing the findings of our study8,17,18. Additionally, a meta-analysis has pointed out that AMD, particularly its late stage, is linked to an augmented risk of CVD mortality19. To explore the correlation between soft drusen and mortality, we conducted a similar investigation using NHANES. Our results indicate a higher prevalence of CVD and hypertension among individuals with soft drusen. Previous research has proposed a connection between CVD, hypertension, and the formation of macular drusen20. The occurrence of drusen is closely related to abnormal lipid metabolism, and some studies have found that drusen are associated with higher levels of high-density lipoprotein21. However, abnormal lipid metabolism is also an important risk factor for CVD, suggesting a heightened likelihood of CVD occurrence in individuals presenting with soft drusen.

Histological studies revealed that soft drusen contain lipoprotein particles of apolipoproteins B and E16. Therefore, investigations have employed the positioning of cholesterol and apolipoprotein B within drusen to examine the supposition that AMD and cardiovascular disease linked to atherosclerosis share common elements and processes connected to lipid deposition outside cells22,23. Additional research has revealed an association between the presence of drusen and heightened risks from the complement factor H gene, as well as two lipid-risk linked allele genes, APOE2 and CETP24. The association of these genes with cardiovascular disease supports a possible link between these two diseases. Our findings are consistent with the above theoretical basis, indicating that soft drusen are highly correlated with CVD, and thus participants with soft drusen have higher CVD mortality.

In this study, participants with soft drusen were older than participants without soft drusen. The reason for the association of soft drusen with CVD mortality and non-CVD or cancer-related mortality is not entirely clear. It is possible that soft drusen reflect a systemic comorbidity associated with frailty and aging, a hypothesis confirmed by several previous studies. A study showed that drusen are associated with aging25. Previous research has established a connection between the presence of drusen and cognitive deterioration26. The work of Chiho Shoda et al. revealed that individuals exhibiting greater levels of cerebral amyloid-β deposition exhibited increased soft drusen areas. This indicates a correlation between soft drusen and Alzheimer’s disease27. Nevertheless, in our investigation, we were unable to delve into this association due to the restricted number of Alzheimer’s disease-related deaths. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) ranked as the primary cause of mortality excluding CVD and cancer. Supporting this link, investigations have revealed a connection where CKD is associated with the presence of peripheral retinal drusen in Korean individuals aged 50 and above, further solidifying the association between drusen and CKD28. However, owing to the restricted number of fatalities resulting from CKD, further examination was impractical in our research.

In addition, it has been hypothesized that the presence of soft drusen with a diameter > 63 μm can cause difficulty in driving at night, difficulty in near work, and glare29. Our findings revealed an increased occurrence of walking disability among patients with soft drusen. Such visual impairments can give rise to various functional complications and psychological issues, including an increased risk of falls30, unintentional injuries31, and a decline in autonomy32. Regrettably, the available data on mortality linked to accidental injuries were insufficient to substantiate this proposition.

This research boasts several strengths, such as the extensive sample size of the elderly cohort, standardized procedures for evaluating soft drusen, and access to extensive demographic data, health indicators, coexisting conditions, and exhaustive mortality records. Nevertheless, there are limitations to consider. Firstly, health practices and concurrent diseases were documented only once, implying that the status of these factors for participants might have altered during the course of the follow-up period. Secondly, while efforts were made to account for multiple confounding factors, including anti- vascular endothelial growth factor treatment, the possibility of unmeasured residual confounders still exists. Nonetheless, the consistency of the HR values above 1 across all subgroup analyses strengthens the validity of our findings.

Conclusions

The investigation revealed that separate categories of soft drusen, including those categorized as distinct or indistinct soft drusen and those measuring 500 μm or more, were individually linked to all-cause mortality, CVD mortality, and mortality resulting from non-cardiovascular and non-cancerous conditions. These outcomes propose a potential shared etiology between soft drusen and CVD. Furthermore, soft drusen might serve as an indicator of systemic pathological comorbidities, symbolizing frailty and aging processes. Elucidation of these connections and the underlying mechanisms warrant further investigation.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are available at NHANES website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

References

Sarks, S. H. Ageing and degeneration in the macular region: a clinico-pathological study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 60, 324–341 (1976).

Hageman, G. S. et al. An integrated hypothesis that considers drusen as biomarkers of immune-mediated processes at the RPE-Bruch’s membrane interface in aging and age-related macular degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 20, 705–732 (2001).

Fei, Y. et al. Quantifying cardiac dysfunction and valvular heart disease associated with subretinal drusenoid deposits in age-related macular degeneration. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 1, 11206721241244413 (2024).

Csincsik, L. et al. Peripheral retinal imaging biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study. Ophthalmic Res. 59, 182–192 (2018).

Boon, C. J. et al. The spectrum of phenotypes caused by variants in the CFH gene. Mol. Immunol. 46, 1573–1594 (2009).

A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch. Ophthalmol. 119, 1417–1436 (2001).

Fisher, D. E. et al. Age-related macular degeneration and mortality in community-dwelling elders: the age, gene/environment susceptibility Reykjavik study. Ophthalmology 122, 382–390 (2015).

Papudesu, C., Clemons, T. E., Agrón, E. & Chew, E. Y. Association of mortality with ocular diseases and visual impairment in the age-related eye disease study 2: age-related eye disease study 2 report number 13. Ophthalmology 125, 512–521 (2018).

Thiagarajan, M., Evans, J. R., Smeeth, L., Wormald, R. P. & Fletcher, A. E. Cause-specific visual impairment and mortality: results from a population-based study of older people in the United Kingdom. Arch. Ophthalmol. 123, 1397–1403 (2005).

Xu, L., Li, Y. B., Wang, Y. X. & Jonas, J. B. Age-related macular degeneration and mortality: the Beijing eye study. Ophthalmologica 222, 378–379 (2008).

Johnson, C. L. et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: analytic guidelines, 1999–2010. Vital Health Stat. 2, 1–24 (2013).

Bundy, J. D. et al. Social determinants of health and premature death among adults in the USA from 1999 to 2018: a national cohort study. Lancet Public. Health 8, e422–e431 (2023).

Loprinzi, P. D. & Addoh, O. Predictive validity of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association pooled cohort equations in predicting all-cause and cardiovascular disease-specific mortality in a national prospective cohort study of adults in the United States. Mayo Clin. Proc. 91, 763–769 (2016).

Zhu, Z., Wang, W., Keel, S., Zhang, J. & He, M. Association of age-related macular degeneration with risk of all-cause and specific-cause mortality in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005 to 2008. JAMA Ophthalmol. 137, 248–257 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Self-reported cataract surgery and 10-year all-cause and cause-specific mortality: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 107, 430–435 (2023).

Curcio, C. A. Soft drusen in age-related macular degeneration: biology and targeting via the oil spill strategies. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59, 160–181 (2018).

Clemons, T. E., Kurinij, N. & Sperduto, R. D. Associations of mortality with ocular disorders and an intervention of high-dose antioxidants and zinc in the age-related eye disease study: AREDS Report 13. Arch. Ophthalmol. 122, 716–726 (2004).

Gangnon, R. E. et al. Effect of the Y402H variant in the complement factor H gene on the incidence and progression of age-related macular degeneration: results from multistate models applied to the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 130, 1169–1176 (2012).

Xin, X., Sun, Y., Li, S., Xu, H. & Zhang, D. Age-related macular degeneration and the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Retina 38, 497–507 (2018).

Hogg, R. E. et al. Cardiovascular disease and hypertension are strong risk factors for choroidal neovascularization. Ophthalmology 115, 1046–1052 (2008).

Lin, J. B., Halawa, O. A., Husain, D., Miller, J. W. & Vavvas, D. G. Dyslipidemia in age-related macular degeneration. Eye (Lond.) 36, 312–318 (2022).

Malek, G., Li, C. M., Guidry, C., Medeiros, N. E. & Curcio, C. A. Apolipoprotein B in cholesterol-containing drusen and basal deposits of human eyes with age-related maculopathy. Am. J. Pathol. 162, 413–425 (2003).

Curcio, C. A., Millican, C. L., Bailey, T. & Kruth, H. S. Accumulation of cholesterol with age in human Bruch’s membrane. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 265–274 (2001).

Thomson, R. J. et al. Subretinal drusenoid deposits and soft drusen: are they markers for distinct retinal diseases? Retina 42, 1311–1318 (2022).

Sano, T., Arai, H. & Ogawa, Y. Relationship of fundus oculi changes to declines in mental and physical health conditions among elderly living in a rural community. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 41, 219–229 (1994).

Lindekleiv, H. et al. Cognitive function, drusen, and age-related macular degeneration: a cross-sectional study. Eye (Lond.) 27, 1281–1287 (2013).

Shoda, C. et al. Relationship of area of soft drusen in retina with cerebral amyloid-β accumulation and blood amyloid-β level in the elderly. J. Alzheimers Dis. 62, 239–245 (2018).

Choi, J., Moon, J. W. & Shin, H. J. Chronic kidney disease, early age-related macular degeneration, and peripheral retinal drusen. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 18, 259–263 (2011).

Scilley, K. et al. Early age-related maculopathy and self-reported visual difficulty in daily life. Ophthalmology 109, 1235–1242 (2002).

Nevitt, M. C., Cummings, S. R., Kidd, S. & Black, D. Risk factors for recurrent nonsyncopal falls. A prospective study. Jama 261, 2663–2668 (1989).

Ivers, R. Q., Mitchell, P. & Cumming, R. G. Sensory impairment and driving: the Blue mountains Eye Study. Am. J. Public. Health 89, 85–87 (1999).

Chiang, P. P., Zheng, Y., Wong, T. Y. & Lamoureux, E. L. Vision impairment and major causes of vision loss impacts on vision-specific functioning independent of socioeconomic factors. Ophthalmology 120, 415–422 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants of the NHANES databases.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Feng Jiang, Xinghong Sun and Mengru Su conceived the conception and design of the study. Huihui Wu and Xiaofang Wang collected and analyzed the data. Xinghong Sun and Huihui Wu prepared the manuscript. Yajun Liu, Ruiwen Cheng and Ye Zhang edited the manuscript. All authors approved the submitted and final versions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Wang, X., Liu, Y. et al. Association of soft drusen with risk of all-cause and specific-cause mortality in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005 to 2008. Sci Rep 14, 28577 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80275-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80275-8