Abstract

Organic nitrates, as effective donors of the signaling molecule nitric oxide, are widely applied in the pharmaceutical industry. However, practical and efficient methods for accessing organic nitrates are still scarce, and achieving high regiocontrol in unactivated alkene difunctionalization remains challenging. Here we present a simple and practical method for highly regioselective halonitrooxylation of unactivated alkenes. The approach utilizes TMSX (X: Cl, Br, or I) and oxybis(aryl-λ3-iodanediyl) dinitrates (OAIDN) as sources of halogen and nitrooxy groups, with 0.5 mol % FeCl3 as the catalyst. Remarkably, high regioselectivity in the halonitrooxylation of aromatic alkenes can be achieved even without any catalyst. This protocol features easy scalability and excellent functional group compatibility, providing a range of β-halonitrates (127 examples, up to 99% yield, up to >20:1 rr). Notably, 2-iodoethyl nitrate, a potent synthon derived from ethylene, reacts smoothly with a variety of functional units to incorporate the nitrooxy group into the desired molecules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

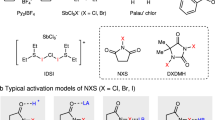

Alkenes, as one of the most abundant and inexpensive chemicals, offer the advantages of wide availability and low cost for organic synthesis1. For instance, ethylene, a key hydrocarbon, is exceptionally affordable with an annual production exceeding 200 million metric tons2. Consequently, the direct difunctionalization of alkenes, which allows for the incorporation of two functional groups into the double bond in a single step, represents an immensely powerful strategy for accessing complex molecules, as evidenced by numerous elegant studies3,4,5. A central challenge in these transformations is controlling the regioselectivity of olefin addition, which is further complicated by unactivated alkyl-substituted C=C bonds that exhibit poor regioselectivity due to their limited electronic and steric bias. To address this, several primary strategies have been employed to promote regioselective difunctionalizations of aliphatic olefins (Fig. 1a): (1) auxiliary control6,7,8, using directing groups to coordinate and stabilize the metal center in the presumed organometallic species; (2) reagent control9,10,11, using specific reagents that dictate the regioselectivity of the reaction; (3) complex catalytic systems12,13,14,15,16,17, employing complex catalysts and/or complex reaction conditions. Therefore, the development of simple and efficient strategies to achieve difunctionalization of alkyl alkenes with high regioselectivity represents a challenging and appealing research goal. Furthermore, although various functional groups such as halogens18,19,20, hydroxyl21, OAc22,23, azido24,25, amino26, trifluoromethyl27, cyano28, alkyl29, aryl30,31, alkynyl32,33, carboxyl34,35, etc., have been successfully introduced into double bonds through the difunctionalization of alkenes (Fig. 1a), there is still a significant demand for the introduction of other useful and attractive motifs into alkenes to access their corresponding derivatives.

Organic nitrates, which serve as potent donors of the signaling molecule nitric oxide (NO), find wide application in pharmaceuticals and bio-active molecules36,37,38, as exemplified by well-known drugs such as glycerol trinitrate and isosorbide mononitrate. Moreover, hybrid drugs formed by combining the nitrooxy group with drug molecules can exhibit synergistic effects or significantly reduce the side effects of drugs while enhancing their efficacy39,40,41,42. Despite their importance, there are limited efficient methods for the synthesis of organic nitrates, particularly for the nitrooxylation of alkenes. Previous methods have often relied on metallic or toxic reagents such as mercury nitrate43, chlorine nitrate44, thionyl nitrate45, pyridinium bromide nitrate46, ceric ammonium nitrate47,48, silver nitrate49, or copper nitrate50 as the nitrooxy source, resulting in harsh reaction conditions or a limited substrate scope. Recently, Tobias and co-workers achieved the hydronitrooxylation of α-alkenes with aqueous nitric acid via visible-light catalysis to produce the corresponding organic nitrates with moderate to high regioselectivities51 (Fig. 1b). This elegant work represents a significant advancement in the development of synthetic methods for organic nitrates.

On the other hand, halogens are fundamental elements in pharmaceutical and chemical industries52,53. For example, over 250 chlorine-containing drugs were approved by the FDA and available on the market in 201954, and halogens (such as chlorine, bromine, and iodine) play a crucial role in numerous important chemical transformations55. Given their significance and broad utility, developing an efficient and practical method for simultaneously introducing the nitrooxy group and halogen into alkenes using readily available nitrooxylating reagents to achieve regioselective olefin halonitrooxylation remains highly attractive.

As part of our continuing research in hypervalent iodine chemistry56,57,58,59,60, we have recently introduced a class of highly active noncyclic hypervalent iodine nitrooxylating reagents (1), which were easily prepared from aryliodine diacetates and aqueous nitric acid56. Additionally, we discovered that the trimethylsilyl (TMS) group can efficiently convert reagents 1 into the corresponding active intermediates56. Motivated by these discoveries, herein we report an efficient and regioselective halonitrooxylation of alkenes using the combination of reagent 1 and TMSX (X = Cl, Br, and I) (Fig. 1c). This protocol exhibits remarkable reactivity, high regioselectivity, and broad substrate generality. Styrene derivatives as substrates exhibit complete regioselectivity under catalyst-free conditions, while the halonitrooxylation of alkyl alkenes in the presence of a catalytic amount of FeCl3 yield the corresponding products with high regioselectivities. Notably, this method is easily scalable to gram quantities and is suitable for late-stage modification of drug molecules.

Results

Optimization of reaction conditions

We began the investigation by choosing dodec-1-ene as the model substrate. Initially, dodec-1-ene reacted with nitrooxylating reagent 1a/TMSCl directly at 0 °C in dichloromethane, getting the excepted product 2 in 82% yield with poor regioselectivity (3.8:1 rr) (Table 1, entry 1). Subsequently, a series of metal salts were evaluated as catalysts (see the details in SI), and it was found that FeCl3 could enhance the regioselectivity (>20:1 rr) but decreased the yield to 42% (Table 1, entry 2). Lowering the reaction temperature to −40 °C increased the yield of product 2 to 76% with 16:1 rr (Table 1, entry 3). Due to the high reactivity of reagent 1a, we hypothesized that increasing the stability of the reagents 1 might improve the reaction yield by appropriately reducing the reaction rate. Previous studies indicated that incorporating electron-withdrawing groups into the phenyl group of 1 could enhance the stability of reagents 156. Therefore, we synthesized a series of reagents 1 with electron-withdrawing groups and found that the substituent and its position significantly affected the yield and selectivity of the reaction (Table 1, entries 3–17). Using the 4-CF3-substituted reagent (1d) as the nitrooxy source improved the yield of product 2 to 83% with >20:1 rr (Table 1, entry 6). Surprisingly, when the catalyst loading was reduced to 0.5 mol %, the target product 2 was still obtained in 82% yield with >20:1 rr (Table 1, entry 18).

Substrate scope

Having established the optimal conditions for chloronitrooxylation, we proceeded to evaluate the scope of unactivated alkenes. Mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra-substituted unactivated alkenes all underwent the chloronitrooxylation reaction smoothly (Fig. 2a). Simple alkyl alkenes (1-dodecene, 1-tridecene, 1-hexene) afforded the corresponding chloronitrooxylation products (2–4) with good yields (74–82%) and excellent regioselectivity (>20:1 rr). The allylbenzene and butenylbenzene also got the corresponding products (5–6) in 64–98% yields with excellent regioselectivity (≥20:1 rr). Substrates bearing numerous substituents such as Br, Cl, OAc, and aldehyde groups were tolerated under the reaction conditions, affording the products (7–13) in 53–99% yields with high regioselectivities (17:1 rr to >20:1 rr). A series of alkenes containing substituted phenyl esters (with F, Ph, CF3, Ac, Ms(mesyl), NO2, Br, I, tBu, or Me group) obtained the desired products (14–24) with regioselectivity ranging from 13:1 to >20:1. Substrates bearing heterocycles such as thiophene and phthalimide achieved the corresponding products (25–26) in 57–64% yield with 15:1–17:1 regioselectivity. 1,1-Di-, tri-, and tetra-substituted alkenes were compatible, yielding the corresponding products (27–31) with excellent regioselectivities. Deca-1,9-diene reacted with double equivalent amounts of 1d/TMSCl to yield the desired product 32 in 62% yield with high regioselectivity. Additionally, the reaction of cyclic alkenes (cyclopentene, cyclohexene, norbornene) in the absence of FeCl3 proceeded stereoselectively, affording the respective trans-adducts (33–35) in 55–78% yields. Interestingly, bromonitrooxylation or iodonitrooxylation of alkenes also proceeded effectively using TMSBr or TMSI instead of TMSCl, yielding several representative products (36–44) with comparable yields and relatively lower regioselectivities (for 36–39). Surprisingly, ethylene and 1-butene smoothly underwent halonitrooxylation to get the corresponding vicinal halo-nitrates (45–50) in 63–97% yields.

Reaction conditions: Condition A: substrate (alkene) (0.20 mmol), 1d (0.6 equiv), TMSX (1.2 equiv), FeCl3 (0.5 mol %), CH2Cl2 (2 mL), −40 °C, 2 h; Condition B: substrate (alkene) (0.20 mmol), 1a (0.6 equiv), TMSX (1.2 equiv), CH2Cl2 (2 mL), 0 °C, 2–5 min. Yields were for isolated and purified products. Regioisomeric ratios were determined by 1H NMR spectra of the crude reaction mixtures. aSee Supplementary Figs. 1–4 for details. Ac acetyl; Ms methanesulfonyl, tBu tert-butyl, Boc tert-butyloxy carbonyl, Bn benzyl, Fmoc fluorenylmethyloxy carbonyl.

After investigating the reactions of various alkyl alkenes, we then explored the substrate scope of activated alkenes (Fig. 2b). Aromatic alkenes reacted smoothly with nitrooxylating reagent 1a and TMSCl at 0 °C without any catalyst, affording the desired products with complete regioselectivities. The reactions performed well with a series of styrenes, regardless of electronic nature (e.g. Me, tBu, OAc for electron-rich groups; halogens, NO2, CF3, CO2Me, CN for electron-deficient groups; CH2Cl, Ph for electron-neutral groups) in the para position, affording the corresponding products (51–64) in 62–89% yields. Styrenes bearing substituents in the ortho and meta position were also compatible with the protocol to provide the desired products (65–68) in comparable yields (67–78%). Styrenes containing multiple substituents in the phenyl group reacted well to yield products 69–73 in 50–83% yields, and 2-vinyl naphthalene was converted to the corresponding product 74 in 71% yield. Hetero-aromatic alkenes such as 3-vinylbenzofuran and 2-vinylpyridine were also tolerant of the reaction conditions to get product 75 in 21% yield and product 76 in 26% yield, respectively. 1,1-Disubstituted aromatic alkenes were efficient substrates, furnishing products 77–80 in 39–94% yields. Although acyclic 1,2-disubstituted substrates only yielded products 81–83 with poor diastereoselectivity, cyclic substrates produced trans-adducts (84–87) with excellent regio- and diastereo-selectivity. Moreover, trisubstituted and tetrasubstituted alkenes gave the corresponding products 88–90 in 37–79% yields. In addition, m-divinylbenzene and p-divinylbenzene underwent double reactions by doubling the amount of reagents, affording products 91 and 92 with high regioselectivities and poor diastereoselective ratios, respectively. Fortunately, 1, 3-enynes as the substrates were converted into the corresponding products 93 and 94 in moderate yields. Furthermore, using TMSBr and TMSI instead of TMSCl, the corresponding difunctionalization of styrenes was also conducted well. Several representative substrates underwent the reaction to yield the expected bromonitrooxylation products 95–100 and iodonitrooxylation products 101–105, respectively. The structures of products were further confirmed by single-crystal X-ray structure analysis of 61 and 84.

To highlight the versatility of our protocols, we investigated their applicability to a variety of complex substrates (Fig. 2c). Initially, we synthesized a range of alkenes by introducing styrenyl or aliphatic alkenyl units onto pharmaceuticals or bioactive molecules via a common and efficient condensation reaction (see SI). Encouragingly, these substrates, bearing diverse scaffolds such as pharmaceutical ingredients, sugars, purine nucleosides, amino acids, and peptides, were well-tolerated in the chloronitrooxylation process, yielding the desired products 106–126 in 45–93% yields with at least 13:1 rr. Notably, the bromonitrooxylation and iodonitrooxylation of complex substrates proceeded smoothly, yielding the corresponding products 127 and 128, respectively.

Synthetic utilities

Moreover, the methods can be easily scaled up to gram scale (Fig. 3a). Several reactions were chosen to test the effectiveness, yielding the vicinal chloronitrate 2 (1.65 g, 78% yield, >20:1 rr), 106 (1.72 g, 87% yield), and vicinal bromonitrate 100 (2.45 g, 81% yield). Additionally, 2-iodoethyl nitrates (41, 47) were obtained in 0.97 g (94% yield) and 10.34 g (95% yield), respectively. Compound 106 can be further transformed into a series of derivatives, including vicinal chloroalcohol 129 (83% yield), vicinal chloroether 130 (75% yield), vicinal chlorothiocyanate 121 (90% yield), vicinal chloroazide 132 (33% yield), and vinylazide 133 (83% yield), through smooth reactions (Fig. 3b).

a Scale-up reaction of chloro-, bromo-, and iodo-nitrooxylation. b Synthetic applications of 106. c Synthetic applications of 47. aScale-up reaction was carried out based on Condition A depicted in Fig. 2. bScale-up reaction was carried out based on Condition B depicted in Fig. 2. THF tetrahydrofuran, DMSO dimethyl sulfoxide, rt room temperature, DMF N,N-dimethylformamide, Cbz benzyloxycarbonyl.

Surprisingly, 2-iodoethyl nitrate (47) serves as a powerful synthetic precursor for introducing a nitrooxy group into molecules61. Various compounds bearing nitrooxy groups 134–147 were easily prepared via nucleophilic substitution of diverse pharmaceuticals/functional groups with 2-iodoethyl nitrate using K2CO3 as a base (Fig. 3c). Significantly, nicorandil (143)62, a medication used to treat and reduce chest pain caused by angina, was synthesized from nicotinamide in 33% yield63.

Mechanistic studies

To gain a preliminary understanding of the reaction mechanism, several control experiments were conducted. Adding a radical inhibitor such as 1, 4-benzoquinone (BQ) or 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ) to the model reaction using dodec-1-ene or 4-bromostyrene as the substrate resulted in the corresponding product 2 or 56 in comparative yields, respectively (Fig. 4a). Notably, the inhibition of the reaction by TEMPO is likely due to its induction of the decomposition of reagent 1, thereby preventing the reaction (Fig. 4a). In addition, a series of competitive experiments using para-substituted styrenes were performed (Fig. 4b). The Hammett plot (log(kR/kH) versus σ) displayed a linear correlation with a ρ value of −2.34 (R2 = 0.99)64,65. The good linearity, along with the results of the radical inhibition experiments mentioned above, implies that the reaction proceeds through an electrophilic route.

We conducted density functional theory (DFT) calculations (The DFT calculation data are provided in the Source Data) to understand the reaction pathway. The computational visualizations, illustrated in Fig. 5a, demonstrate that the formation of the iodonium ion intermediate is less energetically favorable when it arises from the cleavage of the Cl-I bond (Int2’-51 and Int2’-4) compared to the NO3-I bond breaking (Int2-51 and Int2-4) by 11.83 kcal/mol for styrene (51-S) and by 7.76 kcal/mol for 1-hexene (4-S), suggesting the improbability of the iodonium forming through chlorine displacement. Subsequent reaction steps indicated that the nitrate ion is capable of a direct attack on the iodonium intermediate. With 1-hexene, this leads to computed transition state energy barriers of 13.58 kcal/mol for the primary carbon (TS1’-4) and 7.06 kcal/mol for the secondary carbon (TS1-4). For styrene, the barriers are estimated at 16.27 kcal/mol for the primary carbon (TS1’-51) and 8.57 kcal/mol for the benzyl carbon (TS1-51). Clearly, Markovnikov selectivity is more evident with styrene, partly due to the larger differential in energy between the Markovnikov and anti-Markovnikov processes. Moreover, the low energy barriers for the reactions with 1-hexene signify that they proceed speedily at room temperature, which reduces kinetic selectivity.

The addition of FeCl3 has shown fascinating effects, as depicted in Fig. 5b. The calculations suggest that FeCl3 has a stronger binding affinity to the nitrate ion (Int4) by approximately 5 kcal/mol compared to chloride (Int4’), enhancing the stabilization of the resulting iodonium ion. This stabilization leads to a decrease in energy for the iodonium intermediates of styrene (Int5-51) and 1-hexene (Int5-4) by 1.02 kcal/mol and 4.08 kcal/mol respectively. This implies that due to the nitrate being stabilized by FeCl3, the energy barriers for the subsequent nitrate addition ring-opening reactions increase. For 1-hexene, the barriers for the Markovnikov (TS2-4) and anti-Markovnikov (TS2’-4) ring openings are 14.78 and 24.47 kcal/mol, respectively. For styrene, these barriers sit at 16.98 and 23.45 kcal/mol (TS2-51 and TS2’-51, respectively). It is evident that the substantial energy barriers for the anti-Markovnikov process sufficiently retard the reactions at room temperature, significantly enhancing selectivity.

A plausible reaction mechanism was proposed based on the experimental results and previous related reports56,66,67 (Fig. 5c). Initially, 1a reacts with TMSCl to form active species PhI(ONO2)Cl (Int1) and TMSOTMS. FeCl3 coordinates with the nitrate ion68 in Int1 to form Int4. Species Int4 then reacts with alkyl alkene to generate Int5, which subsequently converts to Int6 via a Markovnikov ring opening. Finally, Int6 undergoes reductive elimination to yield the desired product, along with the release of FeCl3 and the generation of iodobenzene as a byproduct.

Discussion

In summary, we have demonstrated a highly regioselective and practical halonitrooxylation strategy for a wide range of olefins. This protocol offers high efficiency, mild conditions, simple operation, and good compatibility with various functional groups. Especially, the product of ethylene iodonitrooxylation, 2-iodoethyl nitrate, can be combined with a range of natural products and drugs to obtain corresponding nitrooxylated functional molecules. The gram-scale preparation and late-stage modification of bioactive molecules show the potential utility of the method. Further investigations into expanding the method are currently underway in our laboratory.

Methods

General procedure A for the synthesis of β-halonitrates

To a test tube was charged with FeCl3 (0.001 mmol, 0.5 mol %), olefin (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and dichloromethane (2 mL), and the mixture was cooled to −40 °C. Then 1d (0.12 mmol, 0.6 equiv) and TMSX (X = Cl, Br, or I; 0.24 mmol, 1.2 equiv) were added and stirred at −40 °C for 2 h. After the reaction was complete, the crude product was purified by column chromatography (petroleum ether /ethyl acetate = 500/1 – 5/1, v/v) via silica gel to afford the desired product.

General procedure B for the synthesis of β-halonitrates

To a test tube was charged with 1a (0.12 mmol, 0.6 equiv) and dichloromethane (2 mL), and the mixture was cooled to 0 °C. Then olefin (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and TMSX (X = Cl, Br, or I; 0.24 mmol, 1.2 equiv) were added and stirred at 0 °C for 1–5 min. After the reaction was complete, the crude product was purified by column chromatography (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 500/1 – 5/1, v/v) via silica gel to afford the desired product.

General procedure for the synthesis of 134–147

In a test tube, the corresponding substrate (0.2 mmol) was placed and DMF (1 mL) was added. Then, K2CO3 (2.4 mmol, 1.2 equiv) and 2-iodoethyl nitrate (2.4 mmol, 1.2 equiv) were added and stirred. Upon completion of the reaction, 10 mL of EtOAc were added, followed by 10 mL of H2O. The reaction mixture was then extracted and washed three times with H2O (10 mL). The organic layer was washed with brine (20 mL) and was dried with MgSO4. The filtrate was removed under reduced pressure. The crude mixture was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether /ethyl acetate = 50/1 – 1/1, v/v) to yield the substrates.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study, including synthetic procedures, characterization data, further details of computational studies and NMR spectra, are available within the article and the Supplementary Information file, or from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers of CCDC2246338 (for 61), and CCDC2327858 (for 84). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Davarnejad, R. Alkenes - Recent Advances, New Perspectives and Applications (IntechOpen, 2021).

Xu, J.-X., Yuan, Y. & Wu, X.-F. Ethylene as a synthon in carbonylative synthesis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 477, 214947 (2023).

Chen, X., Xiao, F. & He, W.-M. Recent developments in the difunctionalization of alkenes with C–N bond formation. Org. Chem. Front. 8, 5206–5228 (2021).

Li, Z.-L., Fang, G.-C., Gu, Q.-S. & Liu, X.-Y. Recent advances in copper-catalysed radical-involved asymmetric 1,2-difunctionalization of alkenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 32–48 (2020).

Merino, E. & Nevado, C. Addition of CF3 across unsaturated moieties: a powerful functionalization tool. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 6598–6608 (2014).

Jeon, J., Lee, C., Seo, H. & Hong, S. NiH-Catalyzed Proximal-Selective Hydroamination of Unactivated Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 20470–20480 (2020).

Yang, T. et al. Chemoselective Union of Olefins, Organohalides, and Redox-Active Esters Enables Regioselective Alkene Dialkylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 21410–21419 (2020).

Chen, X., Rao, W., Yang, T. & Koh, M. J. Alkyl halides as both hydride and alkyl sources in catalytic regioselective reductive olefin hydroalkylation. Nat. Commun. 11, 5857 (2020).

Hu, X.-S. et al. Regioselective Markovnikov hydrodifluoroalkylation of alkenes using difluoroenoxysilanes. Nat. Commun. 11, 5500 (2020).

Law, J. A., Bartfield, N. M. & Frederich, J. H. Site-Specific Alkene Hydromethylation via Protonolysis of Titanacyclobutanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 14360–14364 (2021).

Rivas, M. et al. One-Pot Formal Carboradiofluorination of Alkenes: A Toolkit for Positron Emission Tomography Imaging Probe Development. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 19265–19273 (2023).

Noten, E. A., Ng, C. H., Wolesensky, R. M. & Stephenson, C. R. J. A general alkene aminoarylation enabled by N-centred radical reactivity of sulfinamides. Nat. Chem. 16, 599–606 (2024).

Shibutani, S., Nagao, K. & Ohmiya, H. A Dual Cobalt and Photoredox Catalysis for Hydrohalogenation of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 4375–4379 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. Co-Catalyzed Hydrofluorination of Alkenes: Photocatalytic Method Development and Electroanalytical Mechanistic Investigation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 4380–4392 (2024).

Saper, N. I. et al. Nickel-catalysed anti-Markovnikov hydroarylation of unactivated alkenes with unactivated arenes facilitated by non-covalent interactions. Nat. Chem. 12, 276–283 (2020).

Liu, C.-F., Luo, X., Wang, H. & Koh, M. J. Catalytic Regioselective Olefin Hydroarylation(alkenylation) by Sequential Carbonickelation-Hydride Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 9498–9506 (2021).

Arceo, E., Montroni, E. & Melchiorre, P. Photo-Organocatalysis of Atom-Transfer Radical Additions to Alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 12064–12068 (2014).

Scheidt, F. et al. Enantioselective, Catalytic Vicinal Difluorination of Alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 16431–16435 (2018).

Lian, P., Long, W., Li, J., Zheng, Y. & Wan, X. Visible‐Light‐Induced Vicinal Dichlorination of Alkenes through LMCT Excitation of CuCl2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 23603–23608 (2020).

Lubaev, A. E., Rathnayake, M. D., Eze, F. & Bayeh-Romero, L. Catalytic Chemo-, Regio-, Diastereo-, and Enantioselective Bromochlorination of Unsaturated Systems Enabled by Lewis Base-Controlled Chloride Release. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 13294–13301 (2022).

Liu, M. et al. Metal-free electrochemical dihydroxylation of unactivated alkenes. Nat. Commun. 14, 6467 (2023).

Tian, B., Chen, P., Leng, X. & Liu, G. Palladium-catalysed enantioselective diacetoxylation of terminal alkenes. Nat. Catal. 4, 172–179 (2021).

Vanhoof, J. R., De Smedt, P. J., Derhaeg, J., Ameloot, R. & De Vos, D. Metal‐Free Electrocatalytic Diacetoxylation of Alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202311539 (2023).

Lv, D. et al. Iron‐Catalyzed Radical Asymmetric Aminoazidation and Diazidation of Styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 12455–12460 (2021).

Bian, K. J., Kao, S. C., Nemoto, D. Jr., Chen, X. W. & West, J. G. Photochemical diazidation of alkenes enabled by ligand-to-metal charge transfer and radical ligand transfer. Nat. Commun. 13, 7881 (2022).

Tan, G. et al. Photochemical single-step synthesis of β-amino acid derivatives from alkenes and (hetero)arenes. Nat. Chem. 14, 1174–1184 (2022).

Wang, F., Qi, X., Liang, Z., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Copper‐Catalyzed Intermolecular Trifluoromethylazidation of Alkenes: Convenient Access to CF3‐Containing Alkyl Azides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 1881–1886 (2014).

Zheng, Y.-T. & Xu, H.-C. Electrochemical Azidocyanation of Alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202313273 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. Polarity Umpolung Strategy for the Radical Alkylation of Alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 8195–8202 (2020).

Wang, H., Liu, C.-F., Martin, R. T., Gutierrez, O. & Koh, M. J. Directing-group-free catalytic dicarbofunctionalization of unactivated alkenes. Nat. Chem. 14, 188–195 (2021).

Wang, Z.-C. et al. Enantioselective C–C cross-coupling of unactivated alkenes. Nat. Catal. 6, 1087–1097 (2023).

Wang, M., Zhang, H., Liu, J., Wu, X. & Zhu, C. Radical Monofluoroalkylative Alkynylation of Olefins by a Docking–Migration Strategy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 17646–17650 (2019).

Frye, N. L., Daniliuc, C. G. & Studer, A. Radical 1‐Fluorosulfonyl‐2‐alkynylation of Unactivated Alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202115593 (2022).

Song, L. et al. Visible-light photocatalytic di- and hydro-carboxylation of unactivated alkenes with CO2. Nat. Catal. 5, 832–838 (2022).

Ju, T. et al. Dicarboxylation of alkenes, allenes and (hetero)arenes with CO2 via visible-light photoredox catalysis. Nat. Catal. 4, 304–311 (2021).

Navale, G. R., Singh, S. & Ghosh, K. NO donors as the wonder molecules with therapeutic potential: Recent trends and future perspectives. Coord. Chem. Rev. 481, 215052 (2023).

Bulbule, L. D., Godge, R. K. & Magar, S. Hydralazine and Isosorbide Dinitrate: An Analytical Review. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 13, 291–295 (2022).

Tsikas, D. & Surdacki, A. Biotransformation of organic nitrates by glutathione S-transferases and other enzymes: An appraisal of the pioneering work by William B. Jakoby. Anal. Biochem. 644, 113993 (2022).

Sharma, R., Joubert, J. & Malan, S. F. Recent Developments in Drug Design of NO-donor Hybrid Compounds. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 18, 1175–1198 (2018).

Kleczkowska, P., Kowalczyk, A., Lesniak, A. & Bujalska-Zadrozny, M. The discovery and development of drug combinations for the treatment of various diseases from patent literature (1980-Present). Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 17, 875–894 (2017).

Kerru, N., Singh, P., Koorbanally, N., Raj, R. & Kumar, V. Recent advances (2015–2016) in anticancer hybrids. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 142, 179–212 (2017).

Huang, Z., Fu, J. & Zhang, Y. Nitric Oxide Donor-Based Cancer Therapy: Advances and Prospects. J. Med. Chem. 60, 7617–7635 (2017).

Barluenga, J., Martinez-Gallo, J. M., Najera, C. & Yus, M. The mercury(II) salt-halogen combination HgX2-Hal2: a versatile reagent for stereoselective addition of Hal-X to alkenes. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 360, 1422–1423 (1985).

Fink, W. Umsetzung von CINO3 mit Olefinen. Angew. Chem. 73, 466–467 (1961).

Hakimalahi, G. H., Sharghi, H., Zarrinmayeh, H. & Khalafi-Nezhad, A. The Synthesis and Application of Novel Nitrating and Nitrosating Agents. Helv. Chim. Acta 67, 906–915 (1984).

Lown, J. W. & Joshua, A. V. Electrophilic additions of bromonium nitrate to unsaturated substrates. Can. J. Chem. 55, 508–521 (1977).

Yang, B. et al. Cerium(IV)-Promoted Phosphinoylation-Nitratation of Alkenes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 360, 4470–4474 (2018).

Nair, V. et al. An efficient bromination of alkenes using cerium(IV) ammonium nitrate (CAN) and potassium bromide. Tetrahedron 57, 7417–7422 (2001).

Xue, Y., Park, H. S., Jiang, C. & Yu, J.-Q. Palladium-Catalyzed β-C(sp3)–H Nitrooxylation of Ketones and Amides Using Practical Oxidants. ACS Catal. 11, 14188–14193 (2021).

Gao, M., Zhou, K. & Xu, B. Copper Nitrate-Mediated Selective Difunctionalization of Alkenes: A Rapid Access to β-Bromonitrates. Adv. Synth. Catal. 361, 2031–2036 (2019).

Kim, J., Sun, X., van der Worp, B. A. & Ritter, T. Anti-Markovnikov hydrochlorination and hydronitrooxylation of α-olefins via visible-light photocatalysis. Nat. Catal. 6, 196–203 (2023).

Benedetto Tiz, D. et al. New Halogen-Containing Drugs Approved by FDA in 2021: An Overview on Their Syntheses and Pharmaceutical Use. Molecules 27, 1643 (2022).

Lin, R., Amrute, A. P. & Pérez-Ramírez, J. Halogen-Mediated Conversion of Hydrocarbons to Commodities. Chem. Rev. 117, 4182–4247 (2017).

Fang, W.-Y. et al. Synthetic approaches and pharmaceutical applications of chloro-containing molecules for drug discovery: A critical review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 173, 117–153 (2019).

Juliá, F., Constantin, T. & Leonori, D. Applications of Halogen-Atom Transfer (XAT) for the Generation of Carbon Radicals in Synthetic Photochemistry and Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 122, 2292–2352 (2021).

Cheng, X. et al. Simple and Versatile Nitrooxylation: Noncyclic Hypervalent Iodine Nitrooxylating Reagent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202302521 (2023).

Chen, Y. X. et al. Azidobenziodazolones as Azido Sources for the Enantioselective Copper-Catalyzed Azidation of N-Unprotected 3-Trifluoromethylated Oxindoles. Org. Lett. 25, 2739–2744 (2023).

Lin, C.-Z. et al. Enantioselective synthesis of 3a-azido-pyrroloindolines by copper-catalyzed asymmetric dearomative azidation of tryptamines. Chem. Commun. 59, 7831–7834 (2023).

Li, B. et al. Zinc-catalyzed asymmetric nitrooxylation of β-keto esters/amides with a benziodoxole-derived nitrooxy transfer reagent. Org. Chem. Front. 7, 3509–3514 (2020).

Wang, C. J. et al. Enantioselective Copper-Catalyzed Electrophilic Dearomative Azidation of beta-Naphthols. Org. Lett. 21, 7315–7319 (2019).

Theodosis-Nobelos, P. et al. Design, Synthesis and Study of Nitrogen Monoxide Donors as Potent Hypolipidaemic and Anti-Inflammatory Agents. Molecules 25, 19 (2019).

Goel, H. et al. Cardioprotective and Antianginal Efficacy of Nicorandil: A Comprehensive Review. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 82, 69–85 (2023).

Barozza, A., Colombo, M., Roletto, J. & Paissoni, P. Process for the manufacture of nicorandil. Patent WO2012089769A1 (2012).

Totherow, W. D. & Gleicher, G. J. Steric effects in hydrogen atom abstractions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 91, 7150–7154 (1969).

Hansch, C., Leo, A. & Taft, R. W. A survey of Hammett substituent constants and resonance and field parameters. Chem. Rev. 91, 165–195 (1991).

Xu, C. et al. Trifluoromethylations of Alkenes Using PhICF3Cl as Bifunctional Reagent. J. Org. Chem. 84, 14209–14216 (2019).

Ge, C. & Chen, C. Diastereo-selective synthesis of CF3-substituted epoxide via in situ generated trifluoroethylideneiodonium ylide. Green. Syn. Catal. 4, 334–337 (2023).

Resce, J. L. et al. Structure of the Fe(salen)ONO2 dimer, a ferric complex with a unidentate nitrate ligand. Acta Cryst. C43, 2100–2104 (1987).

Acknowledgements

This paper is in memory of Professor Lixin Dai. We are grateful for the financial support from the Shuguang program (20SG44) from Shanghai Education Development Foundation and Shanghai Municipal Education Commission, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22371187), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (22ZR1445200), the Chinese Education Ministry Key Laboratory and International Joint Laboratory on Resource Chemistry, the “111” Innovation and Talent Recruitment Base on Photochemical and Energy Materials (D18020), and the Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Green Energy Chemical Engineering (18DZ2254200).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.-H.D. conceived and directed the project. X.C. and Q.Y. conducted most of the experiments including the synthesis of the hypervalent iodine nitrooxylating reagents and substrates. Y.-F.C., S.-H.W., X.-C.S. and D.-Y.K. synthesized some substrates. X.C. drafted the Supporting Information. Q.-H.D. prepared the manuscript and revised the Supporting Information.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, X., Yin, Q., Cheng, YF. et al. Practical and regioselective halonitrooxylation of olefins to access β-halonitrates. Nat Commun 15, 7131 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51655-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51655-5