Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is an important endogenous gasotransmitter, but the bioorthogonal reaction triggered H2S donors are still rare. Here we show one type of bioorthogonal H2S donors, sydnthiones (1,2,3-oxadiazol-3-ium-5-thiolate derivatives), which was designed with the aid of density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The reactions between sydnthiones and strained alkynes provide a platform for controllable, tunable and mitochondria-targeted release of H2S. We investigate the reactivity of sydnthiones‒dibenzoazacyclooctyne (DIBAC) reactions and their orthogonality with two other bioorthogonal cycloaddition pairs: tetrazine‒norbornene (Nor) and tetrazine‒monohydroxylated cyclooctyne (MOHO). By taking advantage of these mutually orthogonal reactions, we can realize selective labeling or drug release. Furthermore, we explore the role of H2S, which is released from the sydnthione-DIBAC reaction, on doxorubicin-induced cytotoxicity. The results demonstrate that the viability of H9c2 cells can be significantly improved by pretreating with sydnthione 1b and DIBAC for 6 h prior to exposure to Dox.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

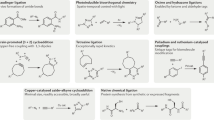

Bioorthogonal reactions have profoundly promoted research in chemical biology and medicinal chemistry over the past two decades1,2,3. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), as an endogenous gasotransmitter4, plays important roles in many physiological processes5,6. Carbonyl sulfide (COS), as a precursor of H2S, can be rapidly hydrolyzed into H2S in the presence of carbonic anhydrase (CA), which is a ubiquitous enzyme in cells7. Although many efforts have been devoted to the development of specific stimuli triggered COS-based H2S donors8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20, the example of biocompatible and targeted H2S release through the bioorthogonal click-and-release reaction is very rare17,20. In 2017, Pluth and coworkers used the click-and-release reaction between thiocarbamate-functionalized trans-cyclooctene (TCO) and tetrazine to deliver H2S through the hydrolysis of COS (Fig. 1a)11. Although the TCO‒tetrazine cycloaddition is super-fast, TCO can easily isomerize in the biological system to generate cis isomer that exhibits low reactivity toward tetrazine3. Moreover, this H2S delivery system is invalid in living cells. Due to the high electrophilicity of tetrazine, the released H2S can be consumed by tetrazine11. In 2019, Taran and coworkers first introduced 1,3-dithiolium-4-olate (DTO) into bioorthogonal chemistry21. DTO can react with strained alkynes, generating a series of thiophene compounds and releasing an equivalent of COS. Leveraging the click-and-release reaction between 5-(4-carboxyphenyl)-2-(4-diphenylaminophenyl)-1,3-dithiol-1-ium-4-olate (Ph2N-DTO) and bicyclo-[6.1.0]-nonyne (BCN) (Fig. 1a), our group developed a COS-based H2S delivery system with a fluorescent thiophene product that allows high spatiotemporal resolution monitoring17. Recently, Xian group and Laughlin group successively developed pyranthione-based click-and-release reaction triggered H2S delivery systems18,20. Pyranthiones (PyrS) can react with BCN through a [4+2] cycloaddition, followed by a retro-Diels-Alder reaction to release a molecule of COS (Fig. 1a). In these two H2S release system, the introduction of a diphenylamino group into DTO (Ph2N-DTO) and a triphenylphosphorium group into PyrS (PPh3-PyrS2) can further realize mitochondria-targeted delivery of H2S in living cells. However, these mitochondria-targeted H2S donors bearing three or four phenyl rings lead to the large molecular size and poor water solubility. In addition, the relatively poor stability of Ph2N-DTO restrained its further biological application, with only 48% of Ph2N-DTO retained after 24 h of incubation in 3% DMSO/PBS at 37 °C17. Mesoionics, a class of five-membered heterocycles, have been employed in organic synthesis and click chemistry21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Sydnthione (1,2,3-oxadiazol-3-ium-5-thiolate), an exocyclic sulfur substituted sydnone analog, was first reported in 197638. However, to the best of our knowledge, the potential of sydnthiones as bioorthogonal reagents has not been explored.

Studies in complex biological systems require bioorthogonal reactions with mutual orthogonalities. In 2012, Hilderbrand and coworkers discovered mutually orthogonal cycloaddition pairs, tetrazine‒TCO and azide‒cyclooctyne, and successfully realized simultaneous imaging of two different types of cancer cells39. Since then, many groups developed a variety of mutually orthogonal reaction pairs to achieve multiple labeling of biomolecules and cells26,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48, and selective delivery of two drugs29. Nowadays, with the aid of density functional theory (DFT) calculations, quite a few bioorthogonal reactions and mutually orthogonal cycloaddition pairs have been established26,29,42,43,44,49,50,51,52,53.

In this work, we design and synthesize a type of mesoionic compound sydnthiones, which holds great promise in developing biocompatible COS-based H2S donors. Sydnthiones can undergo bioorthogonal click-and-release reaction with strained alkyne, and the [3+2] cycloaddition would give rise to an equivalent of COS through the subsequent retro-Diels-Alder reaction (Fig. 1b). We use DFT calculations to predict the reactivities of sydnthione with a series of strained alkenes and alkynes, and discover two bioorthogonal click-and-release reactions of sydnthione with BCN and dibenzoazacyclooctyne (DIBAC), which provides a method for H2S delivery in living cells. More importantly, sydnthione itself shows excellent ability of mitochondrial targeting without any further modification. Furthermore, we identify two bioorthogonal cycloaddition pairs, tetrazine‒norbornene (Nor) and tetrazine‒monohydroxylated cyclooctyne (MOHO), which are orthogonal to the sydnthione‒DIBAC reaction pair. Exploring the orthogonality of the sydnthione cycloadditions to other bioorthogonal reactions would enable us to study the interactions between H2S and other molecules in biological systems. Finally, we verify the feasibility of our approach to release H2S in H9c2 cells and investigated the alleviation effect of H2S on doxorubicin (Dox)-induced cytotoxicity.

Results

DFT calculations on the cycloadditions of N-phenyl sydnthione 1a

In the beginning, we performed DFT calculations on the reaction of N-phenyl sydnthione 1a with DIBAC (Fig. 2a). The [3+2] cycloaddition of 1a with DIBAC through transition state TS1 requires an activation free energy of 21.8 kcal mol−1, and the formation of the bridged intermediate 2 is exergonic by 10.2 kcal mol−1. The subsequent retro-Diels-Alder reaction converts 2 into final pyrazole derivative 3 and COS via TS2 with a barrier of only 3.6 kcal mol−1, which ensures the instantaneous and complete delivery of the desired release product. Therefore, the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition is predicted to be the rate-determining step of this click-and-release reaction. According to the computed reaction barrier of 21.8 kcal mol−1, the second-order rate constant was predicted to be about 0.1 M−1 s−1 in water at 298 K after the empirical energy correction, which would be suitable for a bioorthogonal reaction52. We further investigated cycloadditions of 1a with different strained alkenes and alkynes. As shown in Fig. 2b, the predicted rate constants (k2) range from 10−6 to 10−2 M−1 s−1. Among the eight 2π cycloaddends, DIBAC and BCN are competent partners with sydnthione. However, 3,3-disubstituted cyclopropene (3,3-Cp), Nor, and MOHO are less reactive to sydnthione than DIBAC and BCN based on the predicted rate constants of less than 10−3 M−1 s−1. In addition, tetrazine, a widely used bioorthogonal reagent, reacts rapidly with Nor54 and MOHO55 but not with DIBAC26,39. In light of these results, the sydnthione‒DIBAC click-and-release reaction should be orthogonal to the known tetrazine‒Nor and tetrazine‒MOHO cycloadditions.

a DFT-computed Gibbs free energies for the cycloaddition of N-phenyl sydnthione 1a with DIBAC and subsequent COS release. Energies are reported in kcal mol−1 and second-order rate constants (k2) are in M−1 s−1. b DFT-computed activation free energies for cycloadditions of sydnthione 1a with strained alkenes and alkynes, and the predicted rate constants in water at 298 K. Calculations were performed at the CPCM(water)-M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p)//M06-2X/6-31G(d) level of theory.

Synthesis and reactivities of sydnthiones

Inspired by these predictions, we started to synthesize sydnthiones (Fig. 3). First, sydnones 4a-c were alkylated by the treatment of triethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate. The generated O-ethyl sydnones 5a-c reacted with NaHS in ethanol at −80 °C to give the desired sydnthiones 1a-c (Fig. 3a). With three different N-substituted sydnthiones in hand, we further investigated their reactivities toward DIBAC, BCN, MOHO, and Nor. The kinetics of sydnthiones 1a-c with DIBAC and BCN are summarized in Table 1. It is found that, for the same sydnthione, DIBAC shows better reactivity (about 3-fold) than BCN. When using the same strained alkyne, sydnthione 1b with an electron-withdrawing N-phenyl group reacts about 6 times faster than sydnthione 1c with an electron-donating N-phenyl group. Overall, the reaction of 1b with DIBAC has a largest second-order rate constant of 0.113 M−1 s−1 in 20% DMSO/H2O at 298 K, while the reaction of 1c with BCN has a smallest value of 5.2 × 10−3 M−1 s−1. This means that the release rate of COS can be easily tuned by the electron property of sydnthiones and the employed strained alkynes. Additionally, when sydnthione 1b was incubated with equimolar amounts of MOHO or Nor in 90% DMSO-d6/D2O at 298 K, no reaction was observed even after 24 h (Supplementary Fig. 7). All these experimental results are in good agreement with computational predictions.

Measurement of H2S release by using the methylene blue assay

In order to confirm the feasibility of the sydnthione as a click-and-release reaction triggered H2S donor, we measured H2S release from sydnthione 1b and DIBAC by using the methylene blue (MB) assay. As shown in bar 1–2 of Fig. 4, 1b itself cannot spontaneously release H2S in 20% DMSO/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4, 10 mM) with or without CA. When sydnthione 1b (100 μM) was incubated with different equivalents of DIBAC (1–25 eq.) in 20% DMSO/PBS containing CA (25 μg mL−1) at 37 °C, the concentration of released H2S was enhanced significantly as the equivalents of DIBAC increased (Fig. 4, bar 3–8). Moreover, in the absence of CA or CA being inhibited, much less H2S was observed (Fig. 4, bar 9–10), indicating the H2S generation from the hydrolysis of COS.

1b (100 μM) with different reagents in 20% DMSO/PBS (pH 7.4, 10 mM) at 37 °C during 30 min. (1) 1b only; (2) carbonic anhydrase (CA) (25 μg mL−1); (3) DIBAC (100 μM), CA (25 μg mL−1); (4) DIBAC (500 μM), CA (25 μg mL−1); (5) DIBAC (1.0 mM), CA (25 μg mL−1); (6) DIBAC (1.5 mM), CA (25 μg mL−1); (7) DIBAC (2.0 mM), CA (25 μg mL−1); (8) DIBAC (2.5 mM), CA (25 μg mL−1); (9) DIBAC (1.0 mM); (10) DIBAC (1.0 mM), CA (25 μg mL−1), acetazolamide (AAA) (2.5 μM). Experiments were conducted in triplicate and results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent samples). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Measurement of H2S release in living cells

After investigating H2S release from sydnthione 1b and DIBAC in vitro, we next demonstrated whether the click-and-release reaction could successfully deliver H2S in cellular environments. First, we evaluated the stability and toxicity of sydnthione 1b. After incubating in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)/Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Media (DMEM) or H9c2 cell lysate at 37 °C for 24 h, 82% and 89% of sydnthione 1b remained, respectively (Supplementary Table 1), indicating the excellent stability of 1b. The incubation of HeLa cells with 1b did not show cytotoxicity after 24 h even at concentration of 100 μM (Supplementary Fig. 12). Different from in vitro experiments, we used a fluorogenic H2S probe DCI-CHO-DNP to monitor the liberation of H2S in cells56. DCI-CHO-DNP reacts rapidly with H2S, inducing the cleavage of diaryl ether to generate 2,4-dinitrobenzenethiol and a fluorescence turn-on product DCI-CHO-OH. HeLa cells were pre-incubated with different concentrations of sydnthione 1b (0–30 μM) and DCI-CHO-DNP (10 μM) for 30 min, and then treated with 10 equivalents of DIBAC for another 3 h at 37 °C. As depicted in Fig. 5a, when compared with the endogenous H2S induced red fluorescence, much stronger signals were observed after sydnthione 1b reacting with DIBAC. An increase in concentrations of sydnthione 1b resulted in an enhancement of fluorescence intensities, and there is an excellent linear relationship between them (Supplementary Fig. 18, R2 = 0.994). Furthermore, we measured H2S release from different substituted sydnthiones 1a-c. As shown in Fig. 5b, the click-and-release reactions between three sydnthiones and DIBAC are all able to deliver exogenous H2S in HeLa cells. Under the same reaction conditions, sydnthione 1b showed the strongest red fluorescence, and sydnthione 1c exhibited the weakest signal. This is consistent with the tendency of measured rate constants shown in Table 1. The relative slow kinetics of sydnthione 1c and its excellent stability (Supplementary Table 1) makes it a promising slow-releasing H2S donor for simulating the generation of endogenous H2S, which has potential applications in H2S-based therapeutics57,58,59.

a Fluorescence images of H2S release from different concentrations of sydnthione 1b. HeLa cells were incubated with different concentrations of sydnthione 1b (0–30 μM) and DCI-CHO-DNP (10 μM) for 30 min, and then treated with 10 eq. of DIBAC for 3 h at 37 °C. b Fluorescence images of H2S release from different sydnthiones. HeLa cells were incubated with sydnthione 1a-c (30 μM) and DCI-CHO-DNP (10 μM) for 30 min and then treated with 10 eq. of DIBAC for 3 h at 37 °C. Blank: HeLa only treated with 10 μM DCI-CHO-DNP for 3.5 h. Scale bar = 10 μm. The experiment was independently repeated three times with similar results.

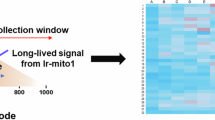

Mitochondria-targeted H2S release in living cells

Previous studies have demonstrated that the role of H2S in cardio-protection is related to mitochondria60. However, the reported mitochondria-targeted H2S donors are rare. AP39, as a known H2S donor, is targeting to mitochondria by the modification of a triphenylphosphorium group61. We introduced a triphenylphosphorium group into the side chain of sydnthione to construct a mitochondria-targeted H2S donor 1d (Fig. 3b). As expected, the H2S release triggered by sydnthione 1d and DIBAC showed a significant colocalization with the commercial mitochondria-targeting probe mito-tracker green with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.88 (Fig. 6, column 1). To our surprise, the H2S releases from sydnthiones 1a-c were also targeting to mitochondria with Pearson’s correlation coefficients of 0.79, 0.78, and 0.74, respectively (Fig. 6, column 2–4). To further evaluate the mitochondria-targeting ability of sydnthione, we synthesized a fluorophore-attached sydnthione 1e (Fig. 3b). Sydnthione 1e has a distinct mitochondrial distribution with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.79, demonstrating that sydnthione itself is mitochondria-targeting and has minor accumulations in other cellular compartments (Supplementary Fig. 25). Experiments above demonstrated that sydnthiones have great mitochondrial affinity. This feature, combined with the good biocompatibility and small size, will expand the use of sydnthione unit as a structural modification in the mitochondria-targeted research.

Dual labeling in living cells

To apply the mutual orthogonality between sydnthione‒DIBAC and tetrazine‒Nor cycloaddition pairs in living cells (Fig. 7a), we synthesized norbornene attached sydnthione 1f (Fig. 3b). When cells were only treated with sydnthione 1f (Fig. 7b, I), we can only detect faint red fluorescence, as a response to the intrinsic endogenous H2S. When we incubated HeLa cells with Tz-504 and DIBAC (Fig. 7b, II), only weak background signals could be detected either. These results demonstrate that no reaction occurs either between sydnthione and Nor or between tetrazine and DIBAC. As shown in Fig. 7a, in the reaction of norbornene-attached sydnthione 1f with DIBAC, only the click-and-release reaction takes place, as evidenced by the distinct red fluorescence in HeLa cells (Fig. 7b, III). Bright green fluorescence can be successfully turned on by the reaction of Tz-504 and 1f (Fig. 7a, b, IV). The joint incubation with 1f, DIBAC, and Tz-504 resulted in both red and green fluorescence labeling in HeLa cells (Fig. 7b, V). These experiments indicated the good selectivity of the H2S release from the sydnthione-DIBAC reaction in the presence of other bioorthogonal reagents, such as tetrazine and norbornene. Furthermore, the inverse-electron-demand Diels-Alder reactions between tetrazine and norbornene have been employed in the delivery of drugs62,63 and radiopharmaceuticals64 for cancer therapy. Since these approaches are orthogonal to our H2S-releasing method, dual-release strategy65 would provide opportunities to investigate the synergistic effect of H2S in therapeutic research.

a Mutual orthogonality between sydnthione‒DIBAC and tetrazine‒Nor bioorthogonal cycloaddition pairs. F: BODIPY. b Dual labeling of living cells. I: HeLa cells were incubated with 1f (30 μM) and DCI-CHO-DNP (10 μM) for 3.5 h at 37 °C. II: HeLa cells were incubated with Tz-504 (30 μM) and DCI-CHO-DNP (10 μM) for 30 min, and then treated with DIBAC (300 μM) for 3 h at 37 °C. III-V: HeLa cells were incubated with 1f (30 μM) and DCI-CHO-DNP (10 μM) for 30 min, then treated with either DIBAC (300 μM, III) or Tz-504 (30 μM, IV) or both (V) for 3 h at 37 °C. Scale bar = 10 μm. The experiment was independently repeated three times with similar results.

Mutually orthogonal release of H2S and Dox in living cells

In 2018, Wang and coworkers utilized the click-and-release reaction between Doxorubicin (Dox)-attached tetrazine (Tz-Dox) and MOHO to liberate Dox55. Our DFT calculations predicted a rate constant of 10−4 M−1 s−1 for the reaction between sydnthione and MOHO (Fig. 2b). This implied a relatively low reactivity, which was later validated by NMR experiments (Supplementary Fig. 7). Therefore, we leveraged the orthogonality between the sydnthione‒DIBAC and tetrazine‒MOHO reaction pairs toward the selective or simultaneous release of H2S and Dox in living cells (Fig. 8a). Before the intracellular experiments, we measured the fluorescence property of Tz-Dox. As the click-and-release reaction between Tz-Dox and MOHO proceeded, fluorescence signals gradually increased (Supplementary Fig. 30), which indicated that the release of Dox can be visualized in living cells. Then we conducted fluorescence imaging experiments to monitor the mutually orthogonal release of H2S and Dox in H9c2 cells (Fig. 8b). Selective release of H2S was achieved when H9c2 cells were incubated with 1b, Tz-Dox, and DIBAC, showing strong red fluorescence of H2S in the presence of probe DCI-CHO-DNP (Fig. 8b, II). Bright green fluorescence signal of Dox was observed by treating H9c2 cells with 1b, Tz-Dox, and MOHO (Fig. 8b, III). If we co-treated the cells with 1b, Tz-Dox, DIBAC, and MOHO, it will result in the concurrent delivery of H2S (red fluorescence) and Dox (green fluorescence) (Fig. 8b, IV). Taken together, we have identified the first example of mutually orthogonal release of gasotransmitter and drug in living cells.

a Mutual orthogonality between 1b‒DIBAC and Tz-Dox‒MOHO reaction pairs. b Images of orthogonal release of H2S and Dox in H9c2 cells. I: H9c2 cells were incubated with 1b (30 μM), Tz-Dox (30 μM), and DCI-CHO-DNP (10 μM) for 3.5 h at 37 °C. II-IV: H9c2 cells were incubated with 1b (30 μM), Tz-Dox (30 μM), and DCI-CHO-DNP (10 μM) for 30 min, and then treated with either DIBAC (300 μM, II) or MOHO (300 μM, III) or both (IV) for 3 h at 37 °C. Scale bar = 10 μm. The experiment was independently repeated three times with similar results.

Sydnthione as H2S donor in attenuating Dox-induced cardiotoxicity

Dox is a widely used broad-spectrum antineoplastic agent. Its clinical use is often limited by the side effect of cardiotoxicity. Previous studies have demonstrated the potential of H2S to attenuate Dox-induced toxicity, when co-delivered or released in advance with the administration of Dox66,67,68,69,70. Here we conducted experiments to investigate the performance of our H2S delivery system in alleviating Dox-induced cardiotoxicity. First, we tested the cytotoxicity of the reaction between 1b and DIBAC on H9c2 cells and showed that it had no obvious effects on cell viability under experimental concentrations (Fig. 9a). Then the effects of simultaneous release of H2S and Dox were explored. H9c2 cells were treated with different concentrations of sydnthione 1b (0–12.5 μM) for 30 min before adding 10 equivalents of DIBAC and 10 μM Dox, and then incubated for additional 24 h. As shown in Fig. 9b, 10 μM Dox would lead to around 30–40% cell loss, while co-releasing H2S was not very efficient to protect cells from Dox toxicity. To our delight, significant improvements in cell viability were observed when H9c2 cells were pretreated with H2S released from 1b and DIBAC for 3 h or 6 h prior to exposure to Dox. (Fig. 9c, d). It was found that the toxicity was distinctly attenuated at concentrations as low as 0.8 μM when pretreated H9c2 cells for 6 h, and with 12.5 μM 1b with DIBAC can almost repair Dox-induced damage. This high efficacy may be due to the mitochondria-targeting H2S release through our delivery system.

a H9c2 cells were treated with 1b (0–12.5 μM) at 37 °C for 30 min, then incubated with 10 eq. DIBAC for 6 h. Cells were then treated with DMSO for additional 24 h. b H9c2 cells were treated with 1b (0–12.5 μM) at 37 °C for 30 min, then incubated with 10 eq. DIBAC and 10 μM Dox for 24 h. c, d H9c2 cells were treated with 1b (0–12.5 μM) at 37 °C for 30 min, then incubated with 10 eq. DIBAC for c 3 h or d 6 h. Cells were then treated with 10 μM Dox for additional 24 h. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent cell pellets). Statistical differences were analyzed by Student’s two-sided t-test between Ctrl and indicated groups. ns, not significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

In summary, we have developed a type of click-and-release reactions between sydnthiones and strained alkynes, which can be used as a H2S delivery system with tunable kinetics. We found that sydnthiones exhibit good mitochondria-targeting ability with high stability, low toxicity and small molecular size. Using this H2S delivery system, we explored the alleviation effects of H2S on Dox-induced toxicity on H9c2 cells. We found that the toxicity was largely reduced after pretreatment with low concentrations (down to 0.8 μM) of 1b and DIBAC for 6 h, it may owe to the advantages of mitochondria-targeted H2S release through our approach. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the sydnthione‒DIBAC reaction is orthogonal to both tetrazine‒Nor and tetrazine‒MOHO cycloadditions, and applied these reactions to selective or simultaneous cell imaging and drug delivery. Overall, we systematically studied the reactivity of sydnthiones and developed a mitochondria-targeting H2S delivery strategy. We believe that sydnthiones will find diverse applications in chemical biology and hold great promise for therapeutics in the future.

Methods

General information

All chemical reagents were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) analysis was performed with silica gel-coated plates with 0.2 mm silica gel-coated HSGF 254 plates. Compounds were purified by column chromatography on silica gel (200–300 mesh).

1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz or 400 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts for 1H NMR spectra are reported as δ in units of parts per million (ppm) downfield from SiMe4 (δ 0.0) and relative to the signal of chloroform-d (CDCl3) (δ 7.26, singlet). Multiplicities were given as: s (singlet); d (doublet); t (triplet); q (quartet); dd (doublets of doublet) or m (multiplets). The number of protons (n) for a given resonance is indicated by nH. Coupling constants are reported as a J value in Hertz. Chemical shifts for 13C NMR spectra are reported as δ in units of ppm downfield from SiMe4 (δ 0.0) and relative to the signal of CDCl3 (δ 77.16, triplet). High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) analyses were performed on an Agilent quadrupole time flight high-resolution mass spectrometer mass spectrometer (6540 Q-TOF LC/MS). Liquid chromatogram was detected by Shimadzu HPLC (LC-20AD, SPD-M20A detector). Analyses were performed using an ACE Excel 5 C18-Amide column (250 × 4.6 mm, id) at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltertrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was performed on a microplate reader (Tcan). Fluorescence spectra were recorded at room temperature by LS55 (PE, America) spectrophotometer from molecular devices using a cuvette with 1 cm path length. Fluorescence microscopy images were taken on an Olympus IX73 fluorescent inverted microscope. Flow cytometry was conducted with Agilent NovoCyte, and data were analyzed and processed using FlowJo.

Computational details

All calculations were performed with Gaussian 0971. Geometry optimizations of all the minima and transition structures were carried out at the M06-2X level of theory72,73,74 with the 6-31 G(d) basis set. Vibrational frequencies were evaluated at the same level to verify that optimized structure is an energy minimum or a transition state and to compute zero-point vibrational energies (ZPVE) and thermal corrections at 298 K. Solvent effects in water were calculated at the M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p) level using the gas-phase optimized structures with the CPCM model75,76,77, where UFF radii were used. The predicted second-order rate constants shown in Fig. 2 were calculated by using the corrected activation free energies [ΔGǂcorr = (ΔGǂcompt + 8.4)/1.6]52, according to Eyring equation at 298 K.

Kinetics measurement

The kinetics of cycloadditions of sydnthione 1 with DIBAC or BCN were measured by HPLC in 20% DMSO/H2O at room temperature. Stock solutions of sydnthione 1, DIBAC, BCN and internal standard in DMSO were prepared. Prepared respective concentration solutions in 20% DMSO/H2O, leading to the final concentration of sydnthione 1 and internal standard were 25 μM, DIBAC and BCN were 250 μM. Reactions were monitored by the absorption peak area of sydnthione 1 as compared with the internal standard. Consumption of materials followed a second-order equation (Eq. (1)) and the second-order rate constants were obtained by least squares fitting of the data to a linear equation. Experiments were conducted in triplicate, and results are expressed as mean ± standard derivation (SD) (n = 3).

[A]: concentration of sydnthione 1 (M)

[B]0: initial concentration of DIBAC (M)

k2: second-order rate constant (M−1 s−1)

The kinetics of cycloaddition of sydnthione 1b with DIBAC at 37 °C was measured by HPLC in 20% DMSO/PBS (pH 7.4, 10 mM). Stock solutions of sydnthione 1b and DIBAC in DMSO were prepared. Prepared respective concentration solutions in 20% DMSO/PBS (pH 7.4, 10 mM), leading to the final concentration of sydnthione 1b was 100 μM and DIBAC was 1 mM. Reactions were monitored by the absorption peak area of sydnthione 1b. Consumption of materials followed a second-order equation (Eq. (1)) and the second-order rate constants were obtained by least squares fitting of the data to a linear equation. Experiments were conducted in triplicate, and results are expressed as mean ± standard derivation (SD) (n = 3 independent samples).

Detection of H2S release in living cells

Cells were seeded in 4-Chamber Glass Bottom Dish and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Test compound was dissolved in DMSO to prepare a stock solution. After attachment, HeLa cells were pre-incubated with sydnthione and DCI-CHO-DNP for 30 min, then treated with DIBAC at 37 °C. Then the cells were washed and the microscopy images were taken on using the red channel (excitation: 540–580 nm, emission: 590 nm to near-infrared) with 60× magnification on an Olympus IX73 fluorescent inverted microscope.

Mitochondria-targeted delivery of H2S in HeLa cells

Cells were seeded in 4-Chamber Glass Bottom Dish and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Test compound was dissolved in DMSO to prepare a stock solution. After attachment, HeLa cells were pre-incubated with 30 μM sydnthione and 10 μM DCI-CHO-DNP for 30 min, then treated with 10 eq. of DIBAC for 3 h at 37 °C, washed and treated with 100 nM mito-tracker green for another 30 min. Then the cells were washed, and the microscopy images were taken using the green channel (excitation: 470–495 nm, emission: 510–550 nm) and the red channel (excitation: 540–580 nm, emission: 590 nm to near-infrared) with 60× magnification on an Olympus IX73 fluorescent inverted microscope.

Sydnthione in attenuating Dox-induced cardiotoxicity

H9c2 cells (1 × 104/well) were seeded into 96-well plates and cultured for 24 h. For H2S and Dox were delivered simultaneously, the cells were treated with 1b (0–12.5 μM) at 37 °C for 30 min, then incubated with 10 eq. DIBAC and 10 μM Dox for 24 h. For H2S was delivered first, the cells were treated with 1b (0–12.5 μM) at 37 °C for 30 min, then incubated with 10 eq. DIBAC for 3 h or 6 h. Cells were then treated with 10 μM Dox or DMSO for an additional 24 h. Cell viability was tested by MTT kit (Keygen Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). 50 μL 1 x MTT was added to each well. After incubating at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for another 4 h, the medium was replaced with 150 μL DMSO. Then, absorbance at 490 nm was measured.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The experimental data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information, and from the corresponding author(s) upon request. The data for all graphs generated in this study are provided in the Source Data files. The source data for fluorescence images are available in Figshare https://figshare.com/s/6cc272aa2d58e90ed26d. The Supplementary Calculation Data for this article is available as a separate Supplementary Data file. The HPLC profiles for the stability studies are available as a separate Supplementary Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Devaraj, N. K. The future of bioorthogonal chemistry. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 952–959 (2018).

Nguyen, S. S. & Prescher, J. A. Developing bioorthogonal probes to span a spectrum of reactivities. Nat. Rev. Chem. 4, 476–489 (2020).

Rigolot, V., Biot, C. & Lion, C. To view your biomolecule, click inside the cell. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 23084–23105 (2021).

Wang, R. Two’s company, three’s a crowd: can H2S be the third endogenous gaseous transmitter? FASEB J. 16, 1792–1798 (2002).

Wallace, J. L. & Wang, R. Hydrogen sulfide-based therapeutics: exploiting a unique but ubiquitous gasotransmitter. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 14, 329–345 (2015).

Hartle, M. D. & Pluth, M. D. A practical guide to working with H2S at the interface of chemistry and biology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 6108–6117 (2016).

Mishra, C. B., Tiwari, M. & Supuran, C. T. Progress in the development of human carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and their pharmacological applications: where are we today? Med. Res. Rev. 40, 2485–2565 (2020).

Levinn, C. M., Cerda, M. M. & Pluth, M. D. Development and application of carbonyl sulfide-based donors for H2S delivery. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 2723–2731 (2019).

Steiger, A. K., Pardue, S., Kevil, C. G. & Pluth, M. D. Self-immolative thiocarbamates provide access to triggered H2S donors and analyte replacement fluorescent probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 7256–7259 (2016).

Zhao, Y. & Pluth, M. D. Hydrogen sulfide donors activated by reactive oxygen species. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 14638–14642 (2016).

Steiger, A. K., Yang, Y., Royzen, M. & Pluth, M. D. Bio-orthogonal “click-and-release” donation of caged carbonyl sulfide (COS) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Chem. Commun. 53, 1378–1380 (2017).

Zhao, Y., Henthorn, H. A. & Pluth, M. D. Kinetic insights into hydrogen sulfide delivery from caged-carbonyl sulfide isomeric donor platforms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 16365–16376 (2017).

Zhao, Y., Steiger, A. K. & Pluth, M. D. Colorimetric carbonyl sulfide (COS)/hydrogen sulfide (H2S) donation from γ-ketothiocarbamate donor motifs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13101–13105 (2018).

Zhao, Y., Henthorn, H. A. & Pluth, M. D. Cyclic sulfenyl thiocarbamates release carbonyl sulfide and hydrogen sulfide independently in thiol-promoted pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 13610–13618 (2019).

Hu, Y. et al. Reactive oxygen species-triggered off-on fluorescence donor for imaging hydrogen sulfide delivery in living cells. Chem. Sci. 10, 7690–7694 (2019).

Zhao, Y., Cerda, M. M. & Pluth, M. D. Fluorogenic hydrogen sulfide (H2S) donors based on sulfenyl thiocarbonates enable H2S tracking and quantification. Chem. Sci. 10, 1873–1878 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Design and development of a bioorthogonal, visualizable and mitochondria-targeted hydrogen sulfide (H2S) delivery system. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202112734 (2022).

Cui, Q. et al. Controllable cycloadditions between 2H-(Thio)pyran-2-(thi)ones and strained alkynes: a click-and-release strategy for COS/H2S generation. Org. Lett. 24, 7334–7338 (2022).

Gilbert, A. K. & Pluth, M. D. Subcellular delivery of hydrogen sulfide using small molecule donors impacts organelle stress. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 17651–17660 (2022).

Huang, W., Gunawardhana, N., Zhang, Y., Escorihuela, J. & Laughlin, S. T. Pyranthiones/pyrones: “click and release” donors for subcellular hydrogen sulfide delivery and labeling. Chem. Eur. J. 30, e202303465 (2024).

Kumar, R. A. et al. Strain-promoted 1,3-dithiolium-4-olates-alkyne cycloaddition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 14544–14548 (2019).

Browne, D. L. & Harrity, J. P. A. Recent developments in the chemistry of sydnones. Tetrahedron 66, 553–568 (2010).

Decuypère, E., Plougastel, L., Audisio, D. & Taran, F. Sydnone-alkyne cycloaddition: applications in synthesis and bioconjugation. Chem. Commun. 53, 11515–11527 (2017).

Porte, K., Riomet, M., Figliola, C., Audisio, D. & Taran, F. Click and bio-orthogonal reactions with mesoionic compounds. Chem. Rev. 121, 6718–6743 (2021).

Wallace, S. & Chin, J. W. Strain-promoted sydnone bicyclo-[6.1.0]-nonyne cycloaddition. Chem. Sci. 5, 1742–1744 (2014).

Narayanam, M. K., Liang, Y., Houk, K. N. & Murphy, J. M. Discovery of new mutually orthogonal bioorthogonal cycloaddition pairs through computational screening. Chem. Sci. 7, 1257–1261 (2016).

Narayanam, M. K., Ma, G., Champagne, P. A., Houk, K. N. & Murphy, J. M. Synthesis of [18F] fluoroarenes by nucleophilic radiofluorination of N-arylsydnones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 13006–13010 (2017).

Bernard, S. et al. Bioorthogonal click and release reaction of iminosydnones with cycloalkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 15612–15616 (2017).

Shao, Z. et al. Bioorthogonal release of sulfonamides and mutually orthogonal liberation of two drugs. Chem. Commun. 54, 14089–14092 (2018).

Shao, Z. et al. Design of a 1,8-naphthalimide-based OFF-ON type bioorthogonal reagent for fluorescent imaging in live cells. Chin. Chem. Lett. 30, 2169–2172 (2019).

Richard, M. et al. New fluorine-18 pretargeting PET imaging by bioorthogonal chlorosydnone-cycloalkyne click reaction. Chem. Commun. 55, 10400–10403 (2019).

Porte, K. et al. Controlled release of a micelle payload via sequential enzymatic and bioorthogonal reactions in living systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 6366–6370 (2019).

Dovgan, I. et al. Automated linkage of proteins and payloads producing monodisperse conjugates. Chem. Sci. 11, 1210–1215 (2020).

Narayanam, M. K. et al. Positron emission tomography tracer design of targeted synthetic peptides via 18F-sydnone alkyne cycloaddition. Bioconjug. Chem. 32, 2073–2082 (2021).

Xu, W. et al. Fluorogenic sydnonimine probes for orthogonal labeling. Org. Biomol. Chem. 20, 5953–5957 (2022).

Ribéraud, M. et al. Fast and bioorthogonal release of isocyanates in living cells from iminosydnones and cycloalkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 2219–2229 (2023).

Zhao, R., Chen, Y. & Liang, Y. Bioorthogonal delivery of carbon disulfide in living cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202400020 (2024).

Hanley, R. N., Ollis, W. D. & Ramsden, C. A. Synthesis of 3 new meso-ionic heterocyclic-systems. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun 1976, 306–307 (1976).

Karver, M. R., Weissleder, R. & Hilderbrand, S. A. Bioorthogonal reaction pairs enable simultaneous, selective, multi-target imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 920–922 (2012).

Patterson, D. M., Nazarova, L. A., Xie, B., Kamber, D. N. & Prescher, J. A. Functionalized cyclopropenes as bioorthogonal chemical reporters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18638–18643 (2012).

Sachdeva, A., Wang, K. H., Elliott, T. & Chin, J. W. Concerted, rapid, quantitative, and site-specific dual labeling of proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 7785–7788 (2014).

Tu, J. et al. Stable, reactive, and orthogonal tetrazines: dispersion forces promote the cycloaddition with isonitriles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 9043–9048 (2019).

Kamber, D. N. et al. Isomeric triazines exhibit unique profiles of bioorthogonal reactivity. Chem. Sci. 10, 9109–9114 (2019).

Hu, Y. et al. Triple, mutually orthogonal bioorthogonal pairs through the design of electronically activated sulfamate-containing cycloalkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 18826–18835 (2020).

Xi, Z. et al. Metal- and strain-free bioorthogonal cycloaddition of o-diones with furan-2(3H)-one as anionic cycloaddend. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200239 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Isonitrile induced bioorthogonal activation of fluorophores and mutually orthogonal cleavage in live cells. Chem. Commun. 58, 573–576 (2022).

Peschke, F., Taladriz‐Sender, A., Andrews, M. J., Watson, A. J. B. & Burley, G. A. Glutathione mediates control of dual differential bio-orthogonal labelling of biomolecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313063 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Noncanonical amino acids as doubly bio-orthogonal handles for one-pot preparation of protein multiconjugates. Nat. Commun. 14, 974 (2023).

Liang, Y., Mackey, J. L., Lopez, S. A., Liu, F. & Houk, K. N. Control and design of mutual orthogonality in bioorthogonal cycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17904–17907 (2012).

Kamber, D. N. et al. Isomeric cyclopropenes exhibit unique bioorthogonal reactivities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 13680–13683 (2013).

Yang, J., Liang, Y., Šečkutė, J., Houk, K. N. & Devaraj, N. K. Synthesis and reactivity comparisons of 1-methyl-3-substituted cyclopropene mini-tags for tetrazine bioorthogonal reactions. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 3365–3375 (2014).

Liu, F., Liang, Y. & Houk, K. N. Bioorthogonal cycloadditions: computational analysis with the distortion/interaction model and predictions of reactivities. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 2297–2308 (2017).

Kang, D. & Kim, J. Bioorthogonal retro-cope elimination reaction of N,N-dialkylhydroxylamines and strained alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 5616–5621 (2021).

Devaraj, N. K., Weissleder, R. & Hilderbrand, S. A. Tetrazine-based cycloadditions: application to pretargeted live cell imaging. Bioconjug. Chem. 19, 2297–2299 (2008).

Zheng, Y. et al. Enrichment-triggered prodrug activation demonstrated through mitochondria-targeted delivery of doxorubicin and carbon monoxide. Nat. Chem. 10, 787–794 (2018).

Hong, J., Zhou, E., Gong, S. & Feng, G. A red to near-infrared fluorescent probe featuring a super large Stokes shift for light-up detection of endogenous H2S. Dyes Pigments 160, 787–793 (2019).

Andreadou, I. et al. The role of gasotransmitters NO, H2S, CO in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and cardioprotection by preconditioning, postconditioning, and remote conditioning. Br. J. Pharmacol. 172, 1587–1606 (2015).

Zheng, Y. et al. Toward hydrogen sulfide based therapeutics: critical drug delivery and developability issues. Med. Res. Rev. 38, 57–100 (2018).

Levinn, C. M., Cerda, M. M. & Pluth, M. D. Activatable small-molecule hydrogen sulfide donors. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 32, 96–109 (2020).

Calvert, J. W., Coetzee, W. A. & Lefer, D. J. Novel insights into hydrogen sulfide-mediated cytoprotection. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 12, 1203–1217 (2010).

Szczesny, B. et al. AP39, a novel mitochondria-targeted hydrogen sulfide donor, stimulates cellular bioenergetics, exerts cytoprotective effects and protects against the loss of mitochondrial DNA integrity in oxidatively stressed endothelial cells in vitro. Nitric Oxide 41, 120–130 (2014).

Kannaka, K. et al. Synthesis of an amphiphilic tetrazine derivative and its application as a liposomal component to accelerate release of encapsulated drugs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 27, 3613–3618 (2019).

Kannaka, K. et al. Inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reactions in the liposomal membrane accelerates release of the encapsulated drugs. Langmuir 36, 10750–10755 (2020).

Zeglis, B. et al. Modular strategy for the construction of radiometalated antibodies for positron emission tomography based on inverse electron demand Diels-Alder click chemistry. Bioconjug. Chem. 22, 2048–2059 (2011).

Tu, J. et al. Isonitrile-responsive and bioorthogonally removable tetrazine protecting groups. Chem. Sci. 11, 169–179 (2020).

Wang, X.-Y. et al. Hydrogen sulfide protects H9c2 cells against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 363, 419–426 (2012).

Guo, R. et al. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide protects against doxorubicin-induced inflammation and cytotoxicity by inhibiting p38MAPK/NFκB pathway in H9c2 cardiac cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 32, 1668–1680 (2013).

Liu, M. H. et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting calreticulin expression in H9c2 cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 12, 5197–5202 (2015).

Chegaev, K. et al. H2S-donating doxorubicins may overcome cardiotoxicity and multidrug resistance. J. Med. Chem. 59, 4881–4889 (2016).

Hu, Q. et al. Mitigation of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity with an H2O2-activated, H2S-donating hybrid prodrug. Redox Biol. 53, 102338 (2022).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, revision D.01 (Gaussian Inc., 2013).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241 (2008).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. Density functionals with broad applicability in chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 157–167 (2008).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. Computational characterization and modeling of buckyball tweezers: density functional study of concave–convex π-π interactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 2813–2818 (2008).

Barone, V. & Cossi, M. Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model. J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 1995–2001 (1998).

Cossi, M., Rega, N., Scalmani, G. & Barone, V. Energies, structures, and electronic properties of molecules in solution with the C-PCM solvation model. J. Comput. Chem. 24, 669–681 (2003).

Takano, Y. & Houk, K. N. Benchmarking the conductor-like polarizable continuum model (CPCM) for aqueous solvation free energies of neutral and ionic organic molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 1, 70–77 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFA1503200, Y.L.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22207051, Y.C., 22303027, W.X., and 22077062, Y.L.), and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20220766, Y.C., and BK20230018, Y.L.) for financial supports. We thank the High Performance Computing Center (HPCC) of Nanjing University for doing the numerical calculations in this paper on its blade cluster system.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L., W.X. and Y.C. conceived and supervised the project. W.X. and Y.L. designed the experiments and wrote the paper. W.X., C.T., R.Z., Y.W., H.J., H.A. and Y.C. performed the experiments. W.X. and X.W. performed the DFT calculations.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yanira Mendez-Gomez and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, W., Tang, C., Zhao, R. et al. Sydnthiones are versatile bioorthogonal hydrogen sulfide donors. Nat Commun 15, 10288 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54765-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54765-2